Neymar has completed his heralded transfer from Barcelona to Paris Saint-Germain, doing to football’s transfer-fee record what Usain Bolt has routinely done to world sprint records. PSG and their Qatari backers also foisted on Barca the kind of humble pie not served up at the Nou Camp since the little incident of some player named Luis Figo.

Beyond the hoopla that attended Neymar’s move – and there might still be a pig’s head thrown into the fray when PSG inevitably come calling one night in the Champions League – what does the international transfer of a footballer really involve?

First, the rules and yes, there are rules. FIFA’s regulations on the status and transfer of players are the main ones. The rules of regional associations, UEFA in the case of the Neymar transfer, also apply as do those of the national associations, Spain and France for the Brazilian, of the clubs involved.

Avoiding the sour grapes and burning shirts in Catalonia tonight as well, of course, as some ecstatic accountants smiling all the way to the bank, let us use a less controversial transfer to illustrate how the rules work. But don’t be disappointed; we will come back to Neymar and his reported half-million pounds a week – now don’t you wish you had paid more attention in PE class?

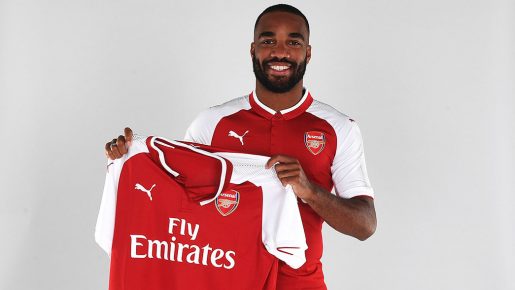

Back in July, on a sunny Sunday in Lyon and typically wet one in London, Jean-Michael Aulas, the president of Olympique Lyonnais sanctioned the transfer of the striker, Alexandre Lacazette, from the French club to Arsenal in the English Premiership. Two days later, on the fourth of July, Lacazette passed a medical at Arsenal’s London Colney training ground. The next day, Arsenal announced the transfer, stating that it was ‘subject to the completion of regulatory processes.’ The transfer fee was reported to be £53 million, a club record for the Gunners. Lacazette signed a five-year contract, hoping to continue an illustrious history of French strikers in Wenger’s time at the club.

The regulatory processes that Arsenal referred to had to do with both clubs complying with FIFA’s transfer matching system (TMS) and the French Football Federation issuing an international transfer certificate (ITC) to the English FA.

The TMS started in 2010. The two clubs involved in a transfer must enter the relevant information into the online TMS and upload certain documents including the transfer agreement and the player’s contract with the new club. Clubs and associations have their own system accounts making it easy for FIFA’s TMS monitors to know who is responsible for any dubious entries.

The ITC, invariably issued online nowadays, is given by the football association of the player’s old club to that of his new club. The English FA had to request and receive Lacazette’s ITC from the French FF before the English FA could register Lacazette as an Arsenal player. Once the English FA made the request of its French counterpart for the ITC however, Lacazette could be registered provisionally in England.

Lacazette’s ITC would have been accompanied by his ‘player passport,’ a document that the FIFA regulations require for each player registered with a country’s football association. The passport lists all the clubs which have had the player on their books from when he was twelve years old. In Lacazette’s case, his player passport had only one previous club, ELCS Lyon, which he joined at seven and left at twelve to Olympique.

By means of the TMS and ITC, a player’s former clubs promptly know of the details of his transfer. They are then able to calculate what, if any, of the transfer fees would come to them as of right. FIFA’s regulations provide for two types of payments to be deducted from transfer fees and paid to all the clubs that trained the player between the ages of twelve and twenty-three

The first payment is ‘training compensation’ which is triggered when a player signs his first professional contract (typically at eighteen years old) and thereafter, every time he is transferred, till he is twenty-three. It is paid, out of the transfer fee, to all the clubs that have trained the player from when he was twelve years old till he was twenty-three. FIFA has a four-category national ranking system that determines the amount of training compensation due to the respective clubs that trained the player.

The second type of trickle down payment is the ‘solidarity payment,’ a flat five percent of the transfer fee whenever a player is transferred internationally throughout his career. It is shared among all the clubs that trained him between the ages of twelve and twenty-three. Each club receives in proportion to the time the player spent with the club but irrespective of the category that the club belongs to in the transfer-ranking system.

Have we confused you enough already? Perhaps there will now be some appreciation of why the Mino Raiolas of this world earn all that money for midwifing transfers.

Anyway, back to Lacazette. Since he was under contract with Lyon, Arsenal would have had to obtain permission from the French side to broach any transfer discussions. In reality, agents, or ‘intermediaries’ as they are now called (proving the one about the rose by any other name) might have first sounded out Lacazette, and possibly, the clubs. The rules frown upon ‘tapping up,’ as these exploratory discussions are called if the player is approached by a covetous club without the knowledge of his employers. You will of course pardon the cackling you just heard – it was from football clubs, intermediaries and players at the mention of tapping up being a naughty thing to do.

The willingness of Lyon and Arsenal (as well as the player) to do a deal opened the door for negotiations to start formally between the clubs on the transfer fee and other terms (such as sell-on bonuses and buyback options). After a fee was agreed between Arsenal and Lyon, Lacazette’s agent, David Venditelli, would then have negotiated personal terms for Lacazette with Arsenal. Venditelli’s fees would also have been negotiated as part of the deal and possibly made payable by Arsenal. The intermediary’s payment is rarely ten percent regardless of what you read in the papers – ‘fake news!’ someone you and I know would scream. The English FA’s recommended fee is three percent.

And so there you have it, a real-life transfer laid bare. You can now fill in the blanks on Neymar’s transfer which did not proceed so jauntily. The rules of Spain’s RFEF introduced a nuance that provided a remarkable moment in transfer history. As he was under contract with a La Liga club, Neymar was obliged to buy out the remainder of his Barcelona contract. The Spanish RFEF would never have issued an ITC unless this requirement was met. Cue therefore sombre men in black showing up at Barcelona’s headquarters with sacks of Euros only to be refused audience for not having an appointment. Well, it went something like that. Really. Happily in the end, joie de vivre prevailed – no laughing at the back, please – and everyone, or okay, almost everyone, shook hands on the deal and lived happily ever after.

For your homework, while PSG sweat on Neymar’s ITC, we ask that you track the clubs now rubbing their hands in glee at the training compensation and solidarity payments that will flow from Neymar’s transfer. Go on. You can Google, can’t you?

Peter Ntephe lives in the US and is a licensed Football Intermediary